Elderly women who fear this will be their last vote, women from minority communities keen to back democratic norms – missing from the electoral list these women feel deprived of their right to vote in what was a historic election.

India’s 2024 general elections, held over two months with 640 million voters participating, concluded last week and it has been described by political observers as the most important since 1977 when the electorate threw out the Indira Gandhi government for its Emergency excesses.

This year too, every vote counted. As we reported from Maharashtra, so crucial was the election for Indian democracy that women activists from traditionally rival political camps campaigned for each other. However, many women, particularly older women and those from minority groups, were denied the right to participate in making electoral history.

On the morning of May 20, 2024, activist and cinematographer Simantini Dhuru headed to the polling booth station at Mumbai South constituency to cast her vote in India’s 18th Lok Sabha elections. For her, voting this year was particularly crucial because she believed it was a fight to save democracy. However, Dhuru could not vote.

“When I went to vote, I found that my name was deleted from the list,” she said.

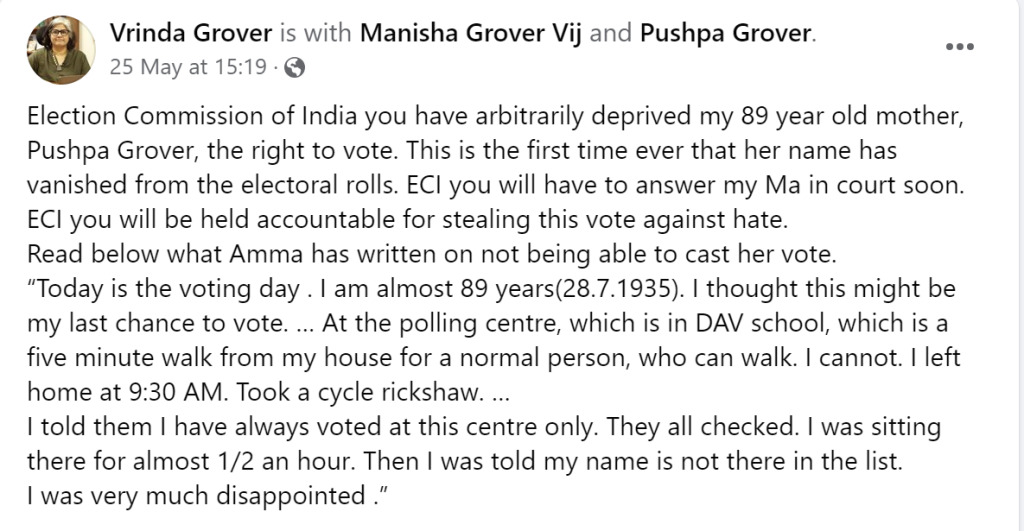

Pushpa Grover, the mother of Supreme Court lawyer and women’s rights activist Vrinda Grover, found her name missing from Delhi’s electoral roll. In a Facebook post, Vrinda shared how her 89-year-old mother, eager to “vote out hate” in what could be her last chance to vote, was disenfranchised.

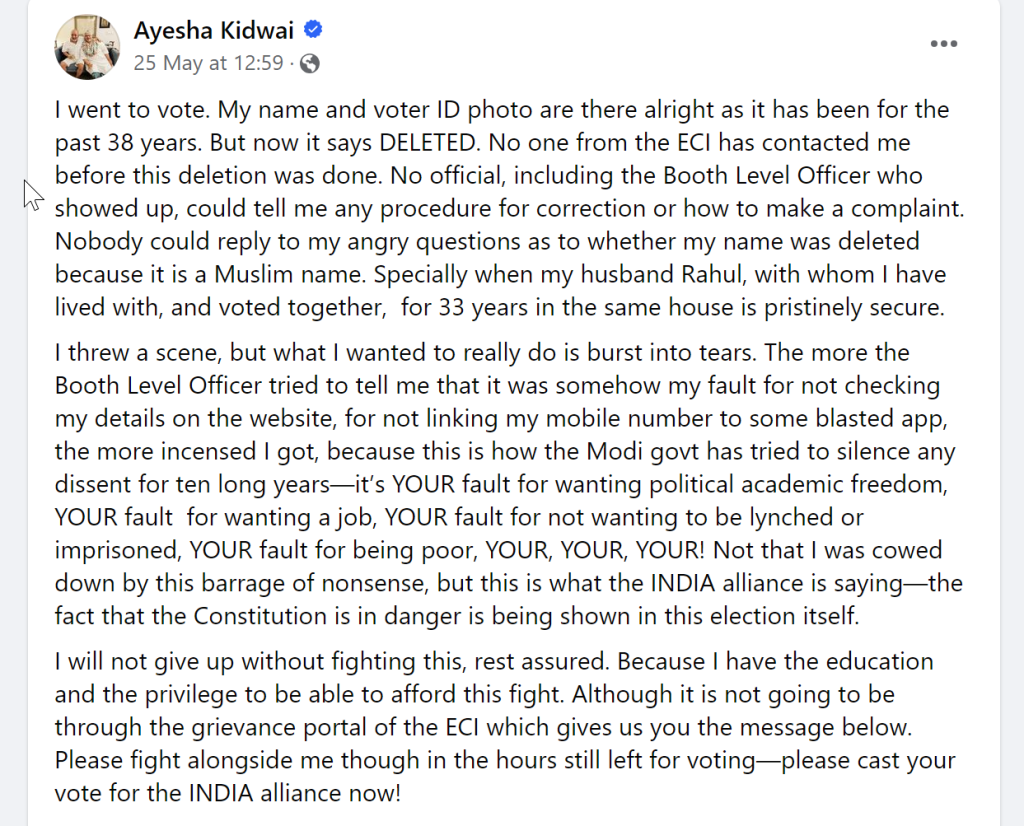

At a polling booth station in Delhi’s Qutub Institutional Area, something similar happened to Ayesha Kidwai, professor of linguistics at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU) and a critic of the Bharatiya Janata Party regime. She had been voting from here for the last 33 years but found her name deleted from the electoral rolls.

“When I approached the booth level officers about it, no one could tell me how to make a correction or how to make a complaint. They kept saying that I should have checked my name in the list first, and [asked] why my Voter ID was not linked to my Aadhar,” she said.

All Kidwai could gather from the officers was that someone had raised an objection to her inclusion in the voter rolls, and demanded that her name be deleted.

As per Rule 18 of the Registration of Electors Rules, 1960, the electoral registration officer (ERO) can accept objections to any name in the electoral roll and delete it if the person is no longer alive, or has shifted residence. But the voter has to be first informed of this, a requirement that the SC had reaffirmed last year.

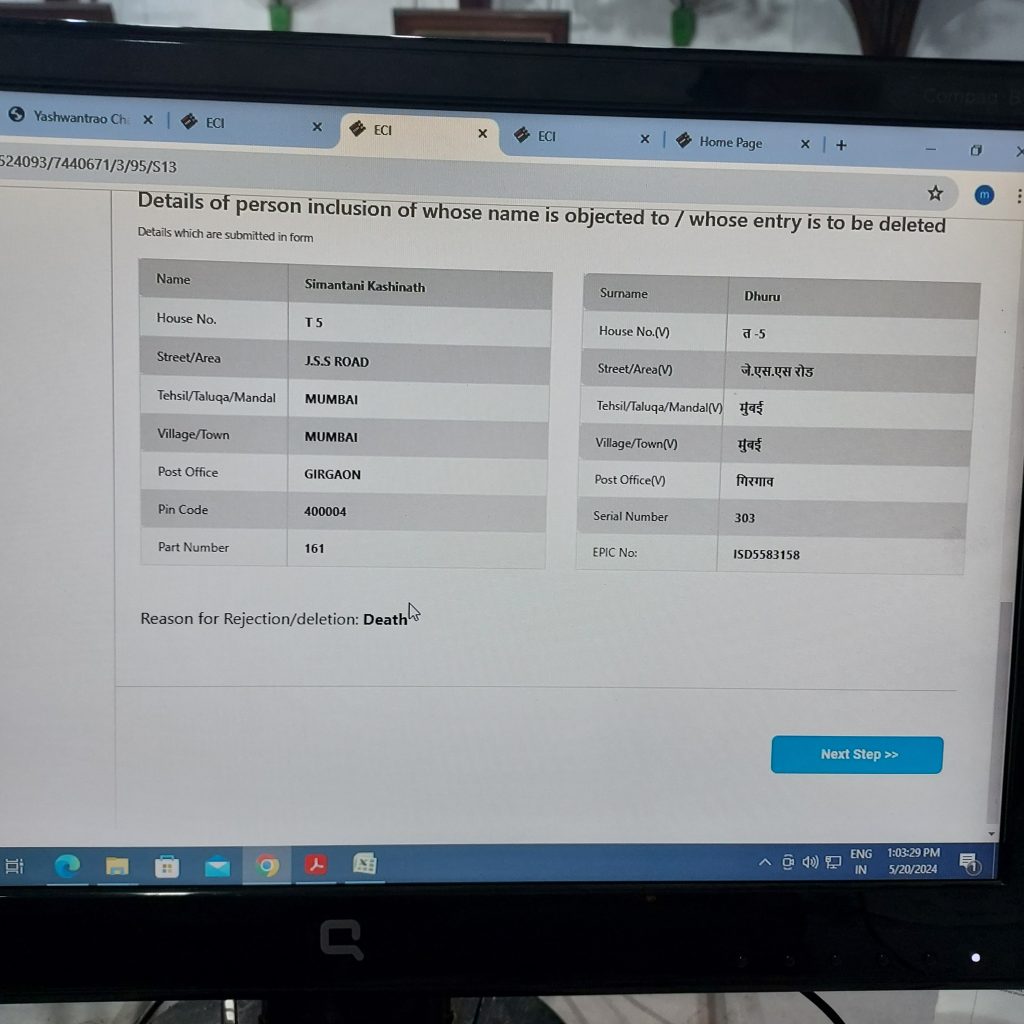

In Dhuru’s case, the polling officers found that her name was deleted because an individual claimed that she was no longer alive. “This is highly disappointing and I am following up with the Election Commission authorities,” said Dhuru.

Dhuru and Kidwai’s accounts are not isolated. Reports show that during this year’s elections, there have been several instances of voter suppression across the country, mostly from Muslim majority areas.

Neither Dhuru or Kidwai were informed by the ERO that their names were deleted from the rolls.

The issue of voter name deletion has been a concern in past elections too. In the 2019 Lok Sabha elections, reports indicated that around 120 million registered voters were missing from the voter rolls. This number included approximately 40 million Muslims and 30 million Dalits. Specific instances of large-scale deletions occurred in states like Andhra Pradesh and Telangana. In Delhi, about 4 lakh voters were deleted from the rolls that year. The 2014 Lok Sabha elections also saw many voters finding their names deleted from the rolls.

‘Eliminating Votes’

“I think this is a deliberate fraud intended to eliminate votes that would have gone against the ruling party and its politics. It is a strategy to cause confusion, to leave room for manipulation to favour the BJP. That is the reason the Election Commission refused to give clear numbers to the Supreme Court in the ADR case but released their data online the next day,” said Dhuru.

On May 9, the Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR), a civil society organisation that had previously challenged the electoral bond scheme, filed a petition seeking a direction to the Election Commision to upload polling station-wise voter turnout data on its website within 48 hours of the conclusion of polling.

ADR’s petition came to light after several political parties and concerned citizens pointed out discrepancies in figures of voter turnout released by the ECI. However, on May 24, the SC refused to direct ECI to publish booth-wise records of voter turnout data.

Kidwai alleged that her name was deleted because she happens to be a Muslim woman. “I feel extremely upset and angry about this. I wanted to vote to say no to Modi, but I was disenfranchised,” said Kidwai.

While Kidwai has no idea and neither was provided any information about the person who raised the objection to her inclusion in the electoral list, Dhuru said she knows. In early January 2024, a person named Keval Chiman Shah sought to have her name off the list, citing her “death”. Her name was deleted on January 9, 2024. She doesn’t know who Keval Shah is.

No Clarification

On the day Delhi went to polls, Tabassum, a resident of north east Delhi’s Sunder Nagri found her name deleted from the voter list. The booth level officer did not clarify why this happened. Aysha, an activist working there says that close to a thousand names in the Muslim majority area are missing from the electoral rolls. Ahead of the Delhi assembly elections, Aysha plans to set up voting camps for them.

Weeks before Tamil Nadu’s Tiruvannamalai constituency went to polls, Ayswarya, 36, a resident of Bangalore went to the taluk office to complain that her name had been deleted from the electoral rolls. Officials told her that the only solution was to create a new voter ID but as the electoral rolls had already been updated, it was too late.

“Some suggested it might be because my Aadhaar wasn’t linked to my voter ID. But we know that it is not mandatory to link one’s voter ID,” said Ayswarya. When electoral officials clean electoral rolls, they delete names of people who have shifted. This is what Ayswarya suspects happened in her case. “They had made a call to my father from whom they got to know that we were no longer residing in Tiruvannamalai. However, they never informed us this is why they were making the call. Also, they didn’t delete his name, only mine.”

Hyacinth Pinto, 60, an architect in the state’s Public Works Department was a presiding officer in a polling booth in Panjim during the last General Elections but her name was still missing from the electoral roll. “It was not only me but several Catholic voters whose names were deleted from the rolls fearing that they wouldn’t vote for the BJP,” alleged Pinto. “Why should the onus be on me to go through the trouble of creating a voter ID?”