In a move to promote cashless society or digitization, the concept of electoral bonds was introduced in the Union Budget 2017. The main aim was to curb use of black money and keep a check on “under-the-table cash transactions”

In an interim order passed on April 12, the Supreme Court has directed all political parties to disclose particulars related to donations received through electoral bonds to the Election Commission. The furnished details have to be submitted in a sealed envelope by May 30, 2019.

This decision assumes significance with the world's largest exercise in democracy already underway.

The apex court further added that this is a ‘weighty issue’ and it would require an in-depth hearing, which cannot be concluded in a limited time. The pleas were filed by the Communist Party of India- Marxist [CPI (M] and NGO Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) against the Narendra Modi government’s inherent anonymity of the particulars under this scheme.

In the light of this development, let us understand what electoral bonds are and how it works.

What is an electoral bond?

An electoral bond (EBs) is a bearer instrument in the nature of a promissory note. In reality, donors can buy the interest-free banking instrument and then transfer them to the account of the political party, where they are converted into donations. This scheme can be purchased by any citizen of India or any company in the country. A person can buy electoral bonds, either singly or jointly, with other individuals.

Price of an electoral bond and how to get it

There is no specified amount or any cap. A bond can be issued in multiples of Rs 1,000, Rs 10,000, Rs 1 lakh, Rs 10 lakh and Rs 1 crore. Electoral bonds are available at specified branches of the State Bank of India (SBI). The donor can simply buy these bonds through a KYC-compliant account. They can select the political party of their choice and contribute, which then is cashed in the party’s verified account within 15 days. They are non-transferable and a one-time payment.

Further, these bonds are available for purchase for a period of 10 days in the months of January, April, July and October, as stated by the central government. An additional period of 30 days are specified in the years of general elections, like 2019.

The donations are also tax deductible; when launched, Finance Minister Arun Jaitley had stated, “A donor will get a deduction and the recipient, or the political party, will get tax exemption, provided returns are filed by the political party.”

Anonymity of donors

Under the electoral bond scheme, the Centre wanted to prevent donors from being associated with any particular party. The motive behind this was to ensure that all donations made to the parties are accounted in the balance sheet without disclosing or exhibiting donor details to the public.

History and norms of electoral bonds

In a move to promote cashless society or digitization, the concept of electoral bonds was introduced in the Union Budget 2017 by the Modi-led government. The main aim was to curb the usage of black money and keep a check on the “under-the-table cash transactions.”

This political funding amelioration was introduced with a promise of bringing in transparency and efforts to cleanse the democratic funding system.

Previous system

Prior to 2017, Section 29C of the Representation of the People Act, 1951 declared the sources of political funding. If donations of more than Rs 20,000 were made, then the Act stated that all registered parties had to declare all donations. But according to experts, a major problem witnessed then was that large donations were usually kept anonymous.

What is the controversy about?

Some political analysts have pointed out that electoral bonds could be the first-of-its-kind instrument in the world for funding of political parties. Jagdeep Chhokar, ADR founder member and trustee, told CNN News18 that while there have been electoral trusts in India, the concept of electoral bonds is new.

The government has been vehemently trying to defend this scheme, arguing that it was introduced in an attempt to “cleanse the system of political funding in the country”. However, the Election Commission has opposed the veil of anonymity associated with such bonds.

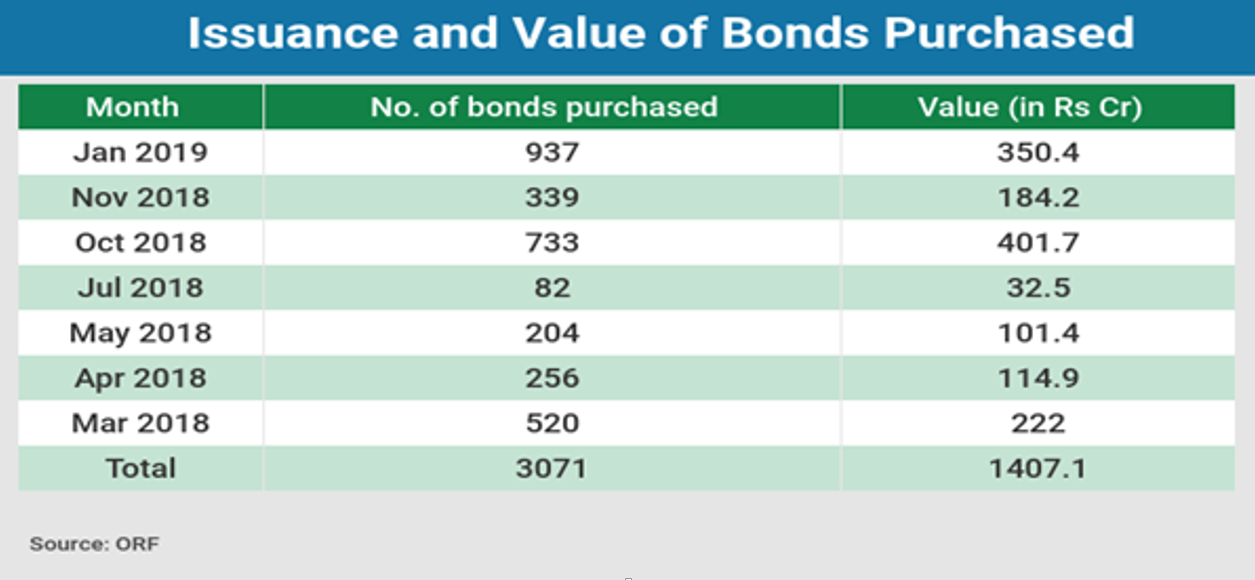

Recently, information obtained under the Right to Information (RTI) Act has revealed that a whopping 99.8 percent of donations received by political parties was through electoral bonds of the highest denominations, the time period being between March 2018 and January 24, 2019. From the data mentioned below, it is evident that electoral bonds have emerged as one of the most sought-after channels for political funding in the country.

Adding to the turmoil, billionaire banker Uday Kotak also questioned Finance Minister Arun Jaitley over his blurred alternative to cash donations for political parties. He asked the minister about his views on electoral reforms and what will be the role of electoral bonds in achieving that goal. In response, Jaitley replied that the debate about this issue is “ill-informed”.

The clamour over electoral bonds has also increased. After the Supreme Court’s judgment last week, the political playground is abuzz on this issue. Former Congress spokesperson Priyanka Chaturvedi took a jibe at the Bharatiya Janta Party (BJP) and said the decision would bring out the "nexus" between the saffron party and its "suited-booted friends".

Reacting to the judgment, BJP spokesperson Nalin Kohli told The Times of India that "whatever the order of the Supreme Court is, it has to be complied with and it is always complied with”.

Non-profit ADR’s report shows that the funding through electoral bonds is biased towards the national parties of the country. The research outlines that Rs 215 crore have been generated through the banking instruments in 2017-18, in which the ruling party has secured Rs 210 crore and the opposition Congress Rs 5 crore.

Future of electoral bonds

With views divided on the issue, early trends suggest the Supreme Court’s decision will be the deciding key factor. Some analysts fear it could distort the country’s electoral process as inviting corporate influence could jeopardize democracy.