The United States of America has recently concluded one of the most heated political races in its history with the election of Donald J. Trump as the next President. India has voided 86% of its currency in circulation and the old ₹500 and ₹1000 notes are no longer legal tender. What do both these events have in common? They are both a consequence of corruption and money in politics.

Donald Trump's mass appeal is based on his platform of anti-establishmentarianism which was accentuated by the fact that his opponent, Hillary Clinton, was seen as a conventional politician funded by big corporations. A lot of people believed that she would work in the interest of the corporations that have funded her campaign and her foundation at the cost of the interests of the American people. The support that the abolition of old high denomination currency has received in India also stems from a similar distrust that the people have developed against "the system."

The common person in the country is frustrated with "black money" and corruption. When people think of black money, they don't think of the streetside paan shop or the local vegetable vendor dealing in cash, they think of big corporates who derive wealth through crony-capitalism and corrupt politicians who support such businesspeople.

A central element of corruption around the world remains the funding of political parties and the money spent during elections. Since the United States of America is widely regarded as the poster child of crony-capitalism, especially after they gave out $700 billion of taxpayer money to corporations after the 2008 financial crisis, it seems like a good candidate for comparing political funding against.

The legislation

In the US, the Federal Election Commission has set limits on the amount of money that individuals can donate to candidates and political parties. Currently, an individual can donate a maximum of $2700 (₹1.8 lakh) to a federal political candidate and $5000 (₹3.4 lakh) per calendar year to a Political Action Committee.

Cash donations to any political entity can't exceed US $100 (₹6800) and any donation above that amount must be made in a written instrument like cheque, money order or bank transfers. Cash donations can only be made anonymously up to $50 (₹3400) and for any donor donating more than that the name, address, employer and occupation are recorded. These records must be forwarded to the Federal Election Commission for any donor whose cumulative contributions exceed $200 for the year.

In India, a political party can take donations up to ₹20,000 ($290) anonymously, and there is no cap on the amount that a political party can receive in cash. For amounts above ₹20,000 a party has to record the donor's name, address, PAN number, mode of payment and date of donation. These details must be furnished to the Election Commission every year to retain the exemption from income tax, but incomplete details seem to attract no penalty.

Corporations are prohibited from contributing in US elections, but companies are still able to contribute through their employees by forming Political Action Committees. No such restriction exists for corporate donations in India and they can freely contribute up to 5% of their average net profits.

A report from the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) shows that 75% of the sources of funding for political parties are unknown.

The US expressly forbids any donation in politics by foreign entities. Indian law did the same under the Foreign Contribution (regulation) Act but it was amended by the government this year to allow for companies with foreign ownership to also donate to political parties.

The reality of donations

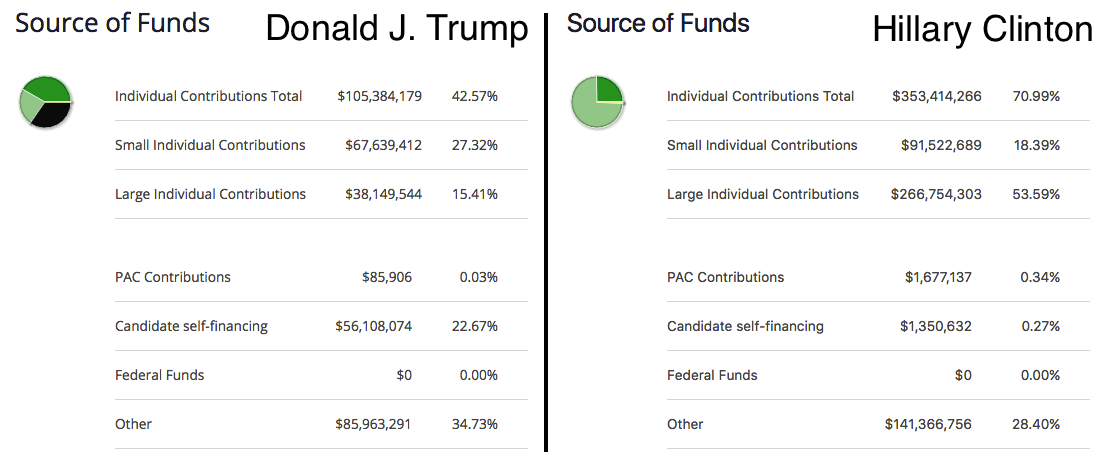

For the 2016 presidential elections in the United States, Hillary Clinton's campaign raised $687 million (₹4671.6 crore) while Donald Trump raised $306.9 million (₹2086.9 crore). Out of this, Trump raised 27.32% from small individual contributions while Hillary raised 18.39% from small contributions.

According to details submitted to the Election Commission of India after the 2014 general elections, the Bharatiya Janata Party spent a total of ₹714 crore while the Indian National Congress spent ₹516 crore for the elections. The official amounts spent in the Indian elections are much less than the unofficial spending, which has been estimated at over ₹10,000 crore (US $1.47 billion).

A report from the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR) shows that 75% of the sources of funding for political parties are unknown. After Prime Minister Narendra Modi's move to void high value currency notes, these filings with the Election Commission become even more important because a massive jump in funding from unknown sources would be a clear indication of money laundering.

As long as politicians need a huge amount of money to win an election, corruption and crony-capitalism will continue.

The median per capita income of the United States is $26,964 while it is $616 for India. In spite of this, India allows an individual to donate over five times more to political parties anonymously. This high limit for anonymous and cash donations seems to be a loophole designed for exploitation by the nexus of crony-capitalists and politicians. If three-fourth of the accounted-for donations to political parties in India are from unknown sources, while small donations are only about one-fourth in the US, it should be obvious that India should reduce its absurdly high limit for anonymous donations.

A fight against black money in India is incomplete without fighting money in politics. As long as politicians need a huge amount of money to win an election, corruption and crony-capitalism will continue. The only way to end this cycle is to eradicate the power that money holds over elections and the first step to that must be reforming the financing of elections.